What Are Tunicates?

Tunicates are enthralling marine animals you've probably seen without knowing it. These filter feeders cover rocks and pier pilings along coastlines worldwide, yet most people walk right past them. At first glance, they might not look like much, but these animals tell an important story about life in the oceans and our own evolutionary history. For starters, there is the fact that they have found ways to thrive in almost every marine habitat.

In this article by thedailyECO, we'll explore what tunicates are, as well as their key features, where they live, how they reproduce, and why scientists find them so interesting.

What are the characteristics of tunicates?

Tunicates are marine animals named for their distinctive protective covering, the tunic. When disturbed, they contract their muscles and shoot out water through their siphons. While many people walk past them on seashores without a second glance, these filter feeders have some surprising features that link them to our own evolutionary past.

Let's explore the key traits that make tunicates stand out among marine invertebrates:

- Tunicates are marine animals that filter water for food through their barrel-shaped bodies. You can spot them by their two siphons, which are tubes that let water flow in and out.

- The tough but flexible covering called a tunic contains a cellulose-like substance that protects their soft internal organs.

- These animals belong to the chordate family, and their larvae have a supporting rod called a notochord in their tails, the same structure human embryos develop.

- As tunicates grow into adults, most lose this feature during a complete body transformation.

- You'll find tunicates living in two main ways: alone or in groups. Some stick firmly to rocks and coral, while others drift freely in ocean currents. The drifting kinds, like salps and pyrosomes, can form chains or colonies stretching several meters long. Their bodies work together, pulsing through the water in coordinated movements.

- Their heart regularly stops and reverses blood flow direction, much like a pump that changes direction every few minutes. Clear or pale yellow blood moves through open spaces in their bodies instead of closed vessels, carrying nutrients wherever needed.

- These filter feeders clean the oceans as they eat. Tiny, hair-like cilia create currents that sweep food particles into mucus nets.

- They process waste differently from most animals too. Instead of using kidneys, they push waste products directly through their body surfaces or store them in special cells.

- Tunicates can reproduce both by splitting off new individuals and through eggs and sperm.Their larvae swim freely before finding a spot to attach and transform into adults. This transformation turns a swimming, tadpole-like creature into a stationary filter feeder, though some species keep swimming their whole lives.

- Their bodies range from transparent to brightly colored, and some species produce their own light through chemical reactions. This bioluminescence helps them communicate or ward off predators. They've also developed other survival adaptations, like quickly shrinking by squeezing out water when threatened.

- Research shows tunicates serve as natural monitors of ocean health by concentrating heavy metals from seawater. Scientists study them for medical research, as their compounds might lead to new medicines.

- Their simple feeding groove became the thyroid gland in vertebrates, showing how basic structures can develop into complex organs over time.

- They can even rebuild their bodies from small pieces, making them valuable subjects for regeneration studies.

Want to understand how marine animals produce their own light? Explore the science behind this natural phenomenon in our comprehensive article.

Types of tunicates

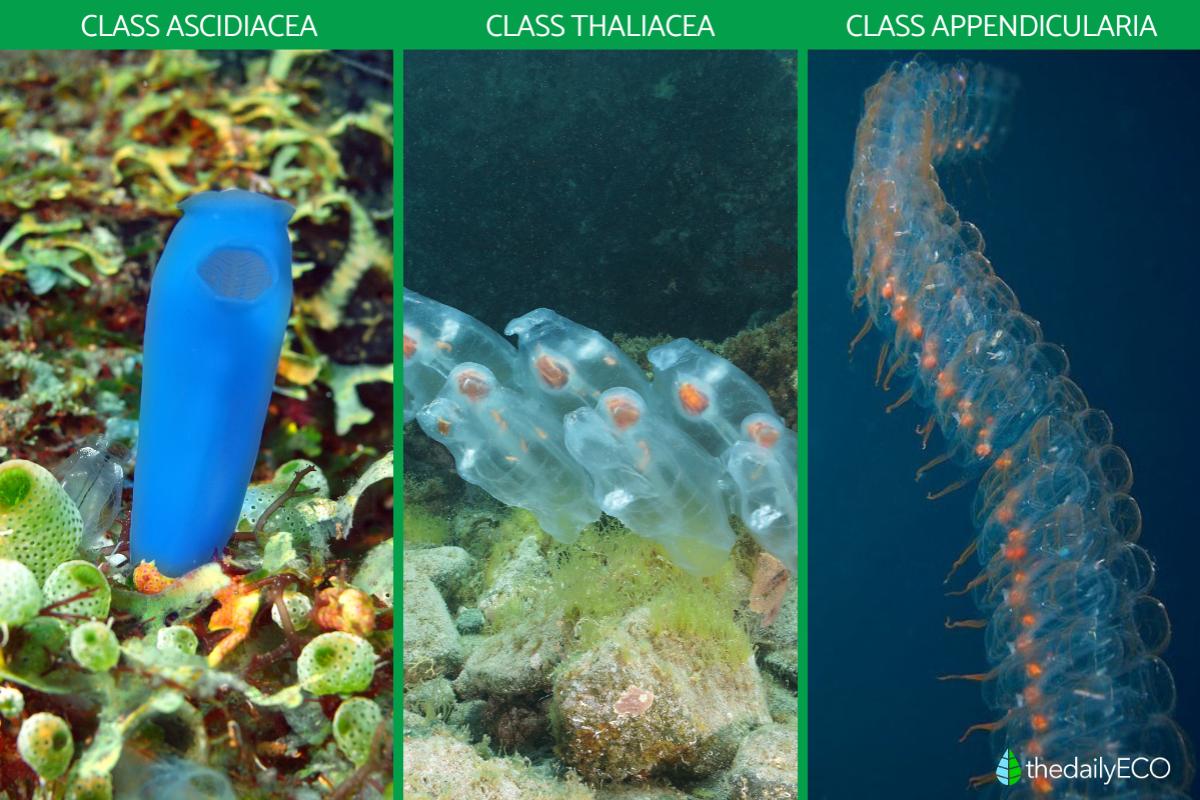

Tunicates fall into three classes that show different ways of life in the oceans:

Class Ascidiacea

Class Ascidiacea makes up the largest group of tunicates.

These sea squirts typically attach to rocks, shells, or other hard surfaces on the ocean floor. As adults, they lose the tail and most of their notochord, which are features they had as larvae. You'll find them living either alone or in colonies, from shallow coastal waters to the deep sea. When touched, they contract their bodies and shoot out water, giving them their common name.

Class Thaliacea

Class Thaliacea includes the salps, doliolids, and pyrosomes. Unlike their bottom-dwelling relatives, these tunicates swim freely in open waters. They move by pumping water through their bodies, creating a kind of jet propulsion. Most have clear, jelly-like bodies and form long chains or colonies. They prefer warm waters and can become very numerous during plankton blooms.

Class Appendicularia

Class Appendicularia sets itself apart by keeping its larval features into adulthood. These small tunicates, usually 2-5 millimeters long, keep their tails throughout their lives.

They build complex "houses" made of mucus that help them filter food from the water. Unlike other tunicates, they always live alone and never form colonies. You can find them from surface waters down to great depths.

Each class has adapted to fill a different role in marine ecosystems. While sea squirts filter feed from fixed positions, salps drift through the oceans in chains, and larvaceans create their own filtering structures. This variety of lifestyles helps tunicates thrive in nearly every marine habitat.

Meet the travelers of the tunicate family and find out how sea salps form incredible chains and help clean our oceans in this related article.

Where do tunicates live?

Tunicates have adapted to live in every corner of the world's oceans, though you'll only find them in marine environments, never in fresh water.

While most species prefer the rich ecosystems of shallow coastal waters (less than 200 meters deep), some have made their home in the darkness of the deep sea, living as far down as 8,000 meters below the surface.

They're particularly common on rocky shorelines and coral reefs, where they can firmly attach to hard surfaces. You'll spot them clinging to natural structures like rocks and shells, but they've also taken well to human-made environments. Many species readily grow on pier pilings, dock structures, and boat hulls. Some prefer the quieter environment of muddy sea floors, while their free-swimming relatives, like salps, roam the open ocean.

Though tunicates live in all temperature zones, from polar seas to tropical waters, most species flourish in warmer regions. Each species typically adapts to specific temperature ranges, which helps explain their distribution patterns across the oceans.

Their success in colonizing so many marine environments has a downside. When carried to new areas on ship hulls or in ballast water, some tunicate species can spread rapidly in their new environment. In these cases, they may overtake local species and become invasive, affecting the ecological balance of their new home.

How do tunicates feed?

Tunicates feed by filtering tiny particles from seawater through their body. Water enters through their oral siphon, carrying plankton, bacteria, and other small organic matter. While many species stay fixed in one place, they don't just wait passively for food. Instead, they actively pump water through their bodies using tiny, hair-like cilia that beat constantly.

The water flows into their perforated pharynx, which works like a fine mesh. Here, their endostyle (a groove in the pharynx wall) produces mucus that traps food particles. This mucus net catches even very small particles that would slip through regular filters. The trapped food moves toward their U-shaped gut, while filtered water exits through their second siphon, called the atrial siphon.

This feeding system works so well that a single tunicate can filter many liters of seawater each day. Some species can capture particles as small as bacteria, making them among the ocean's most effective filter feeders.

Interestingly, free-swimming tunicates, like salps (Salpidae) use the same basic method but can move to areas with more food.

Do tunicates have a stomach?

Yes, tunicates have a stomach. The digestive system in these animals has a relatively simple structure: water and food enter through one opening, nutrients are processed and absorbed, and waste exits near their outflow siphon. This arrangement keeps their living space clean and helps them process large amounts of water efficiently.

How do tunicates reproduce?

Most tunicates can reproduce in two different ways.

In sexual reproduction, they release eggs and sperm into the water, where fertilization occurs. Although most tunicates have both male and female organs, they typically don't self-fertilize. Some species have separate sexes.

The fertilized egg develops into a swimming larva that looks like a tiny tadpole. This stage is brief, lasting only a few hours.

During this time, the larva doesn't feed since it lacks a mouth because. Its only job is to find a good place to settle. Once it finds a suitable spot, it goes through a dramatic transformation. The larva attaches head-first, its tail and other swimming structures get absorbed, and it develops into the barrel-shaped adult with filtering siphons.

Many tunicates can also reproduce asexually by budding. This is when a new individual grows from the parent's body.

Colonial species use this method to expand, and some can even split into fragments, with each piece growing into a new colony. This mix of reproductive strategies helps tunicates spread successfully in marine environments.

Interestingly, sexual reproduction introduces genetic variation, leading to adaptability and evolution. Asexual reproduction, on the other hand, enables rapid population expansion in favorable conditions.

Interested in learning about more ocean inhabitants? Discover the diverse world of amphipods, from sandy beach hoppers to deep-sea dwellers.

If you want to read similar articles to What Are Tunicates?, we recommend you visit our Biology category.

- Baez, AM, & Marsicano, CA (2007). Invertebrate chordates (Phylum Chordata). Félix de Azara Natural History Foundation. II;745-749.

- Encyclopedia of Life (sf) Tunicates. Available at: https://eol.org/pages/46582349/articles?locale_code=show_all