Are a Serpent and a Snake the Same Thing?

Are snakes and serpents the same thing? While they’re often used interchangeably, there are key differences in meaning, usage, and symbolism. In everyday language, both words may refer to the same animal, but “serpent” often carries deeper mythological or religious significance.

In this article by thedailyECO, we’ll explore the real difference between a snake and a serpent, looking at their scientific definitions, cultural meanings, and symbolic roles across history.

What is a snake?

Snakes belong to the suborder Serpentes (sometimes called Ophidia) within the order Squamata, which also includes lizards. These reptiles evolved around 100 million years ago, likely from burrowing lizard ancestors who gradually lost their limbs.

They're distinguished by their elongated, legless bodies covered in overlapping scales. But there's so much more to their unique anatomy:

- A highly flexible jaw that can unhinge to swallow prey much larger than their head.

- A specialized forked tongue that collects airborne particles to "smell" their environment.

- No external ears, sincethey feel vibrations through their jawbones.

- A backbone with anywhere from 200-400 vertebrae, compared to humans that have just 33.

Ever wondered how a creature without legs can move so effectively? Snakes have evolved several locomotion methods including lateral undulation (the classic S-pattern), rectilinear movement (straight-line crawling), sidewinding, and concertina motion. This adaptability is part of what's made them such successful predators across diverse habitats.

All snakes are strictly carnivorous, with diets ranging from insects and small mammals to birds, eggs, and even other reptiles. Their hunting strategies vary widely, since some constrict their prey, others use venom, and some simply overpower and swallow their victims whole.

In terms of reproduction, species exhibit diverse strategies. Oviparous organisms lay eggs, often in nests, for external development. In contrast, ovoviviparous and viviparous species retain developing embryos internally, resulting in live birth

In fact, there are roughly 3,900 species slithering across our planet. Snakes can be found practically everywhere except Antarctica, extremely cold regions, and some islands. Snakes have adapted to deserts, forests, mountains, plains, and even oceans. They're most diverse in tropical regions, with countries like Australia, Brazil, and India hosting particularly rich snake biodiversity.

The venomous question often comes up when people encounter snakes. Only about 600 species, which is roughly 15%, are venomous, and of those, only about 200 can cause significant harm to humans.

From fangs to venom glands, discover the incredible specialized features that make snakes such successful predators.

What is a serpent?

Before we explore the word "serpent" further, it's important to clarify: serpents and snakes are biologically identical. We're not discussing two different animal groups. Every creature called a "serpent" is a snake, and any snake could potentially be called a "serpent" in certain contexts.

The distinction lies entirely in language usage, historical context, and cultural connotations, not in biology or zoological classification. With this understanding, let's examine what makes the term "serpent" distinct from "snake" in our language.

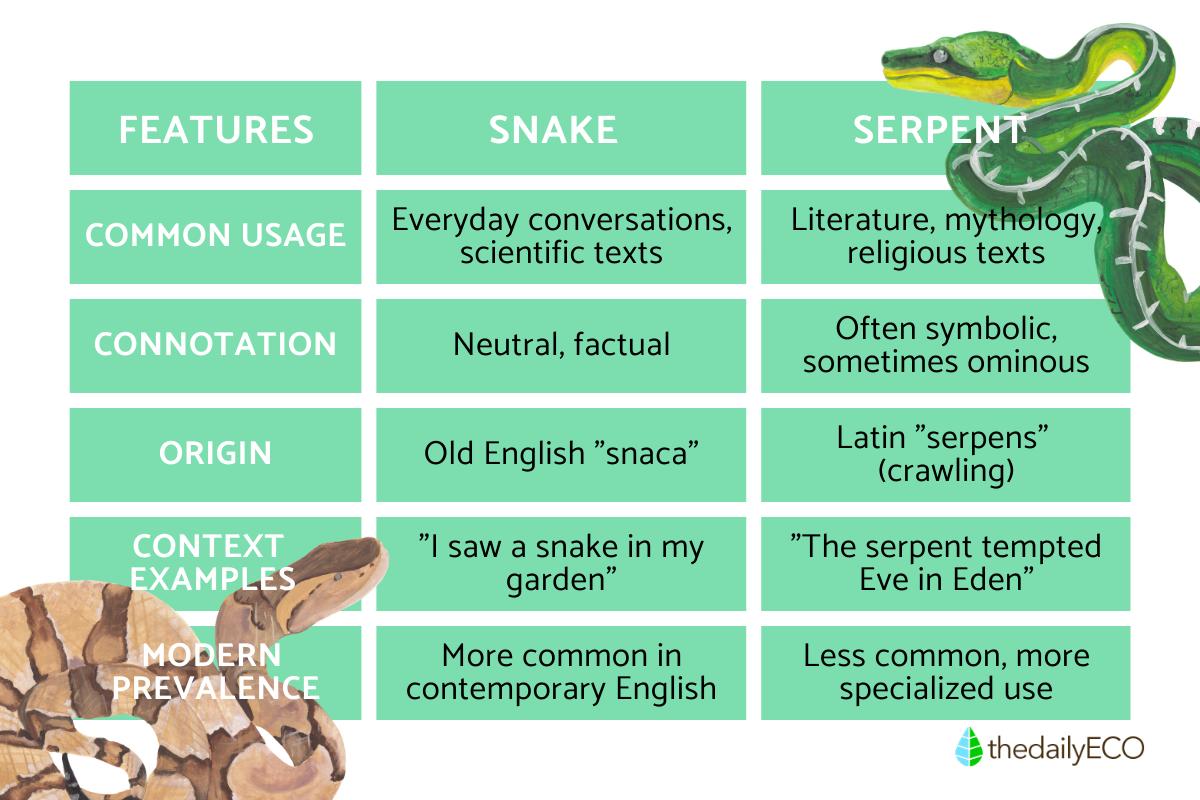

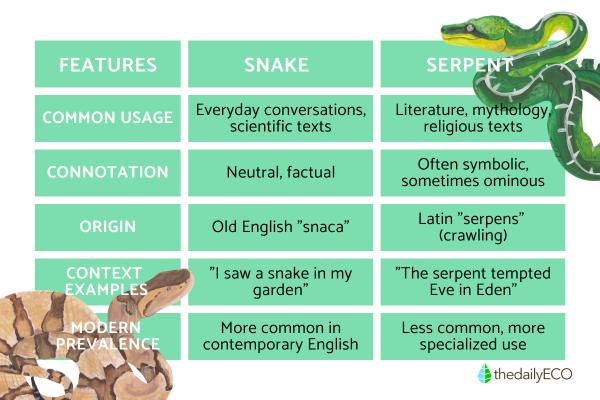

The word "serpent" has a rich linguistic history. It entered English from Old French "serpent," which came from Latin "serpens" (meaning "crawling" or "creeping thing"). This Latin term derives from the verb "serpere" (to creep).

In historical texts, "serpent" was the main term for these reptiles until around the 18th century. Medieval and Renaissance writings rarely used "snake," preferring the Latin-derived "serpent" in scientific, religious, and literary contexts.

In the King James Bible (1611), "serpent" appears dozens of times, while "snake" doesn't appear at all. This reflects how educated writing of the time favored words with Latin or Greek origins, considered more sophisticated.

Today, "serpent" has developed specific connotational territory in our language. While "snake" has become the neutral, everyday term for the animal itself, "serpent" usually appears in contexts that emphasize symbolic, mythological, or archaic qualities. You'd more likely find a "serpent" in fantasy literature, religious texts, or poetic works than in a biology textbook or newspaper article about local wildlife.

The connotations of "serpent" often carry significant emotional and symbolic weight. When someone is described as "serpent-like" or "serpentine," it typically suggests cunning, deception, or treachery rather than simply having physical characteristics resembling a snake. Phrases like "serpent's tongue" (referring to deceitful speech) or Shakespeare's use of "serpent" to describe betrayers and villains show these negative associations, which stem largely from biblical and cultural traditions where serpents symbolize temptation and evil.

Regional variations in the use of "serpent" versus "snake" exist across English-speaking countries, though the general pattern remains similar. In British English, "serpent" might appear slightly more often in everyday speech than in American English, where "snake" is the preferred term in casual contexts. Academic and scientific writing globally has standardized around "snake" for literal descriptions of the animals, reserving "serpent" primarily for historical, literary, or symbolic contexts.

In other languages, the distinction between terms equivalent to "snake" and "serpent" varies. French uses "serpent" as the standard term without the literary distinction English makes. Spanish distinguishes between "serpiente" (the general term) and more specific words like "culebra" (typically for non-venomous species) or "víbora" (for vipers). German uses "Schlange" as the general term, with "Serpent" appearing mainly in literary or religious contexts, similar to English usage.

When to use snake vs serpent

While "snake" and "serpent" identify the same legless reptiles, their usage differs in key ways. Let's break down these differences to understand when each term applies.

In scientific contexts, "snake" is the standard term. Biologists, herpetologists, and zoologists use "snake" in research papers, field guides, and taxonomic classifications. The scientific suborder is officially Serpentes, but when scientists discuss individual animals or species, they say "snake."

The literary record suggests otherwise. Authors often choose "serpent" deliberately for its evocative qualities. In literature, "serpent" carries connotations of mystery, danger, wisdom, or temptation.

Context determines which term fits best. "Snake" works in everyday conversation, educational material, news reports, and scientific discussions. "Serpent" appears in religious texts, mythology, fantasy literature, poetry, and historical writing. The choice often signals to readers what lens—scientific or symbolic—they should apply.

Several misconceptions about these terms need clearing up:

- Serpent refers only to large snakes: size doesn't determine terminology. A small coral snake could be called a "serpent" in the right literary context.

- Serpent means venomous and snake means non-venomous: venomousness has nothing to do with which term applies. Both venomous and non-venomous species can be called either snakes or serpents.

- Serpent refers to prehistoric or extinct species: time period doesn't dictate terminology. Modern species can be "serpents" in the right context.

- Serpent is just an old-fashioned way to say snake: while "serpent" has older origins, both terms remain in active use with different applications.

Curious about how snakes adapted to life in the ocean? Dive into our exploration of these marine reptiles.

If you want to read similar articles to Are a Serpent and a Snake the Same Thing?, we recommend you visit our Facts about animals category.

- Harrington, S. M., de Haan, J. M., Shapiro, L., & Reeder, T. W. (2015). Phylogenetic inference and divergence dating of snakes using molecules, morphology and fossils: new insights into convergent evolution of feeding morphology and limb reduction. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 15(1), 87. https://bmcecolevol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12862-015-0358-5

- Leal, M., & Cohn, M. J. (2017). Development of skin micro-ornamentation in the common house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus) and evolution of scale morphology in squamates. Nature Communications, 8(1), 2192. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-02788-3