Owls have become ingrained in our stories, popping up as symbols of wisdom, spooky omens, or even messengers from other realms. They appear in our myths as symbols of wisdom, omens of death, or messengers from other realms. In Harry Potter, they deliver mail. In Native American traditions, they carry secrets. And in modern science, they continually surprise researchers with their remarkable adaptations.

The following article by thedailyECO we share ten fascinating facts about owls that showcase just how extraordinary these birds truly are.

Owls can swim

Contrary to what you might expect, owls can actually swim when they absolutely have to. However, this isn't something they choose to do voluntarily. When owls have been spotted swimming, it's usually because they've been forced into water by predators or threats.

Their feathers aren't very water-resistant compared to other birds, which makes swimming a desperate last resort rather than a hunting strategy. After such an unexpected dip, owls must spend significant time drying their feathers, which can leave them vulnerable to predators and hypothermia. So if you ever see an owl taking a dip, it's probably having a really, really bad day.

Owls aren’t related to eagles or hawks

Despite their predatory nature and similar hunting adaptations, owls aren't closely related to eagles, hawks, or falcons. Owls belong to the order Strigiformes, which includes two families: Tytonidae (barn owls with their distinctive heart-shaped faces) and Strigidae (all other owls with round faces). Meanwhile, eagles and hawks belong to the family Accipitridae in the order Accipitriformes. This taxonomic separation occurred millions of years ago in their evolutionary history.

The most striking difference? Owls are primarily nocturnal hunters, with specialized adaptations for night vision and silent flight, while most eagles and hawks are diurnal (active during daylight).

Though they share adaptations like sharp talons and keen vision, these similarities evolved independently through convergent evolution rather than from a recent common ancestor. It's a perfect example of how different evolutionary lineages can develop similar traits when facing similar environmental challenges.

Fascinated by those heart-shaped faces? Discover how barn owls differ from their round-faced cousins in our popular companion article.

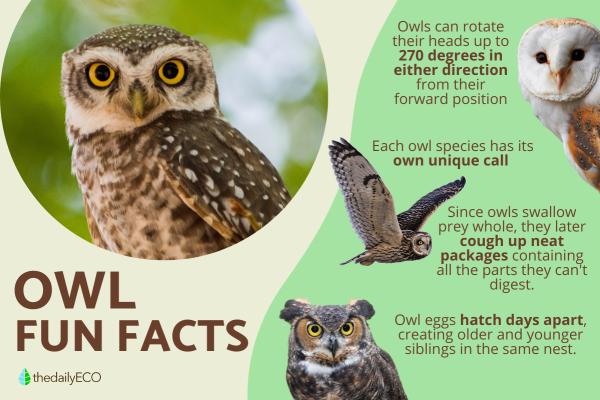

Owls can rotate their heads up to 270 degrees

Owls can rotate their heads up to 270 degrees in either direction from their forward-facing position, that's three-quarters of a full circle. This ability helps compensate for their fixed eye positions. Unlike humans, owls cannot move their eyes within their sockets. Their eyes are actually tube-shaped and fixed in their skull, giving them an intense forward gaze but no peripheral vision.

This extreme neck flexibility isn't a full 360-degree rotation as sometimes claimed, but it's still an extraordinary adaptation that allows them to monitor their surroundings while keeping their body still and hidden from prey. The next time you try to sneak up on an owl, remember it can probably see you even when its back appears to be turned.

Owls have twice as many neck vertebrae as humans

An owl's incredible neck flexibility comes from having 14 vertebrae in their neck, which is exactly twice the number humans have. These extra vertebrae create more points of rotation, allowing for their head movements. For perspective, this vertebrae count is impressive even among birds, it's fewer than swans (which have an astounding 22-25 vertebrae) but more than many other birds.

What makes this even more fascinating is that the structure of owl neck vertebrae differs significantly from ours. In humans, our vertebrae have protective spines that limit rotation to prevent injury. Owl vertebrae lack these limitations in key areas, with the first three vertebrae having spines only on the back rather than the sides. This unique anatomical design creates a much greater range of motion. But vertebrae alone aren't enough, owls also have specialized adaptations in their blood vessels that prevent blood flow from being cut off during extreme rotations.

Owls communicate through distinctive calls

Owls are known for their distinctive hoots and calls, which serve multiple purposes in their social lives. These vocalizations help them identify other owls, establish territory boundaries, and attract mates during breeding season. The acoustic design of these calls is fascinating because many owl species vocalize at unusually low frequencies, which allows their sounds to travel farther through vegetation without being absorbed or distorted.

Each owl species has its own unique vocal signature, creating a veritable symphony of night sounds in owl-rich habitats. The great horned owl produces the classic deep "hoo-hoo-hoo" that many associate with owls, while barn owls emit blood-curdling screeches that have contributed to many a haunted house legend.

These varied vocalizations allow different species to carve out their own acoustic niches in the darkness. Though these sounds might seem spooky to us, they're essential communication tools in the owl world, conveying complex information about territory, mating availability, and identity.

Owls regurgitate indigestible parts of their prey

Since owls lack teeth for chewing, they swallow their prey whole or in large piece. Their specialized digestive system efficiently extracts nutrients from the flesh, but can't process bones, fur, feathers, and other indigestible materials. Instead of passing these materials through their entire digestive tract, owls compact them into pellets that they later regurgitate.

These pellets aren't like other bird droppings, they're dense, dark masses containing all the compressed remains of their meals. An owl typically casts (regurgitates) a pellet about 6-10 hours after eating, often from its favorite roosting spot. The casting process itself is quite dramatic, the owl will bob its head, twist its neck, and open its beak wide to expel the pellet.

These pellets have become valuable scientific tools. Biologists and ecologists can dissect owl pellets to identify exactly what species the owl has been eating, how many individual animals it consumed, and even detect changes in local small mammal populations over time.

Their specialized feathers enable silent flight

One of the owl's most impressive adaptations is their near-silent flight. An owl can fly just inches from your ear and you might never hear it. This acoustic stealth is achieved through multiple specialized feather adaptations that have fascinated both biologists and engineers.

The leading edge of owl wings features a comb-like fringe that breaks up the airflow and reduces sound-producing turbulence. The trailing edge has a soft, flexible fringe that eliminates the noisy air disturbances that most birds create.

Additionally, their wing feathers have velvety surfaces with thousands of microscopic extensions that further dampen sound waves. Even the owl's broad, rounded wing shape plays a role, allowing for slow flight without stalling and minimizing the whooshing sounds typical of other birds.

This silent approach is crucial for hunting success, as their prey, primarily small mammals, have excellent hearing. While a mouse might hear a hawk's wing beats from a distance, they often never detect an owl until it's too late.

Wonder why owls evolved such specialized feathers? Explore the complete picture of feather evolution and adaptation in our reader-favorite guide

Female owls are often larger than males

In many owl species, females are noticeably larger than males, a pattern called reverse sexual dimorphism that contradicts the typical pattern seen in mammals. In some species, like the great horned owl, females can be up to 25% heavier than their male counterparts. This size difference is visible even to casual observers, with females showing larger body mass, wing span, and talon size.

Evolutionary biologists have proposed several fascinating theories for this unusual size difference. The larger female size may provide advantages in nest protection and incubation, as females typically take primary responsibility for these crucial tasks.

Their greater size helps them maintain consistent egg temperatures even in harsh weather conditions. The larger size might also help females maintain better body condition during the demanding breeding season, when they spend long periods on the nest while males bring food.

Another intriguing theory suggests this dimorphism allows owl pairs to divide hunting resources by targeting different prey sizes, males taking smaller, more agile prey while females can overpower larger animals. This niche partitioning might reduce competition between mates and allow a single territory to support both birds more efficiently.

They practice asynchronous hatching

Many owl species practice asynchronous hatching, meaning they don't lay all their eggs at once but rather at intervals of 1-3 days. This results in owlets of different ages and sizes in the same nest. This strategy provides a form of natural insurance. If food is plentiful, all owlets can survive, but during food shortages, the older, stronger owlets will get fed while younger ones might not.

This seemingly harsh strategy actually increases the overall success rate of the brood, ensuring that at least some offspring survive even in tough conditions. In good years, the parents can successfully raise all the chicks, but in lean years, they focus resources on the ones most likely to survive.

Owls are found on every continent except Antarctica

These adaptable birds have successfully colonized nearly every corner of the planet, from dense tropical rainforests to arid deserts and northern boreal forests. The snowy owl thrives in the Arctic tundra, while eagle owls dominate mountainous regions across Europe and Asia.

Burrowing owls have adapted to life underground in the grasslands of North and South America, and screech owls occupy forests throughout the Americas.

Their global distribution speaks to their evolutionary success and ability to fill various ecological niches as predators. Owls have been around for a very long time, fossil records show owl-like birds dating back about 58 million years, making them one of the oldest groups of land bird predators. Their global presence today is a testament to their remarkable adaptability and success as hunters throughout the ages.

Ever wondered how the largest owl would compare to the biggest bird on the planet? The answer might surprise you. Discover the true titans of the avian world in our size comparison guide.

If you want to read similar articles to 10 Fun and Weird Facts About Owls, we recommend you visit our Facts about animals category.

- Enríquez, P.L., Eisermann, K., Motta-Junior, J.C., & Mikkola, H. (2015). A review of the taxonomy and systematics of Neotropical owls. Neotropical Owls: Diversity and Conservation. ECOSUR. Mexico, 29-38.

- Owl Research Institute. https://www.owlresearchinstitute.org/

- McVean, A. (2018). Owls Don't Have Eyeballs. Office for Science and Society. McGill University. https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/did-you-know/owls-dont-have-eyeballs